In British vernacular speech, something ordinary and unremarkable is referred to as “common or garden”, an extension of the practice of referring to plants such as “common lavender” or “garden lavender” to denote that they are not exotic. Some of the plants under this heading are sometimes considered weeds, although some of them, such as dandelion, are such stars I have given them a page of their very own. Others are found in many, if not most, English gardens.

Many plants on this page were self-sown — which is itself a partial misnomer, as very few plants simply sprout where the seeds fall. Most hitch a ride on a shoe, or the fur of a fox or a domesticated cat, or a gust of wind, or in a bird’s beak, or in the digestive tracts of hedgehogs, mice, or badgers, or find their way in through my compost heap. Most owe their existence to pollinators: the bees, flies, wasps and beetles that hover or crawl amongst the flowers. Many — including the hellebores, cyclamen, lamb’s lettuce and wild garlic that carpet the garden each in their season — have self-propagated from an original plant that was a gift. Many others were uninvited — but not unwelcome — strangers. A few were in situ when I moved here 50 years ago.

“What is a weed?” asked Ralph Waldo Emerson. “A plant whose virtues have not yet been discovered”. A person’s attitude toward weeds speaks volumes about their relationship with prediction and control, and their openness to and curiosity concerning the unexpected. I can’t help but draw parallels with attitudes toward human migration. Yes, there are circumstances where certain plants, particularly food crops, want to be prioritised in terms of space, water and soil nutrition; and yes, there are species of plants that are invasive and will “take over the neighbourhood”, but with vanishingly few exceptions, these are easy to manage and within a short time take their place in the ecology of the garden, enhancing the complexity and diversity of the living community. Some help to stabilise the soil and prevent erosion; others provide food and a habitat for wildlife. All improve soil quality by adding organic matter to it, either directly or via the compost heap. Each has its virtues. Many are simply beautiful to have around.

And what is “ordinary”? The connotations of the word are revelatory of the human fondness for novelty. Although the core meaning is simply ‘normal; usual; typical; not different or special or unexpected in any way”, it spills out of this neutral enclosure into implications of value — usually negative, but very occasionally positive. We might, for example, describe someone fondly as “an ordinary guy”, suggesting he’s not a raving lunatic, or a serial killer, or merely eccentric to an extreme degree, along the same lines as Douglas Adams’ description of Earth as “mostly harmless”.

More likely, ‘ordinary’ implies unimportant, insignificant, dull, mediocre — even vulgar. Indeed, as the Latin vulgaris simply means ‘common’, countless specific names of many species include the term, e.g. aquilegia vulgaris, primula vulgaris.

That ‘familiarity breeds contempt’ is a very old idea, documented as early as the 5th century but probably as old as humanity itself. We value least the things which are most familiar, which also tend to be the things we most rely on for our thriving and even our survival. It makes sense that our nervous systems are hard-wired to pay attention to novelty — because something out of the ordinary may be a threat. But to value the unusual and exotic over the everyday undermines intimacy, community, and stable connections of all kinds.

Familiarity need not breed contempt. One of pioneers of American Zen, Suzuki Roshi, spoke of “beginner’s mind”, which sees with fresh and appreciative eyes, imagining many possibilities.

That is how I hope you will approach not only these images, but their subjects as you encounter them in your own everyday, ordinary — but never insignificant or mediocre — lives.

Mullein

Marigold

Clematis montana 'Elizabeth'

Lilac

Bellis daisy

Daffodil

Poppy

Fuchsia

Comfrey

Comfrey

Crocosmia

Bracken fern

Foxglove

Forsythia

Lady's mantle

Bladder campion

Grape hyacinth

Japanese anemone

Lesser celandine

Marigold

Hellebore

Peony

Azalea

Peony 'Sarah Bernhardt'

Peony

Poppy

Anemone

Plantain

Plantain

Roseum allium

Pulmonaria

Pulmonaria

Stachys

Snowdrop

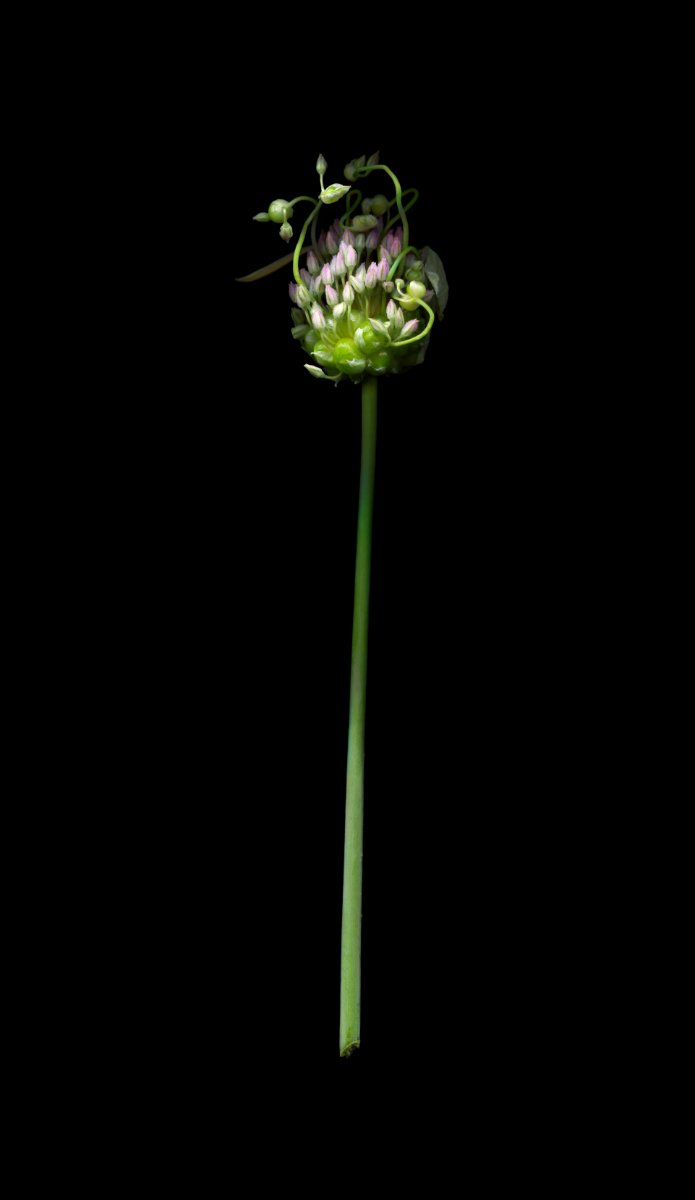

Tree onion

Tree onion

Cyclamen

Wisteria sinensis

Crocosmia

Chaenomeles (ornamental quince)

Aconite

Honeysuckle

Japanese anemone

Akebia

Comfrey

Lesser celandine

Lily of the valley

Lilac